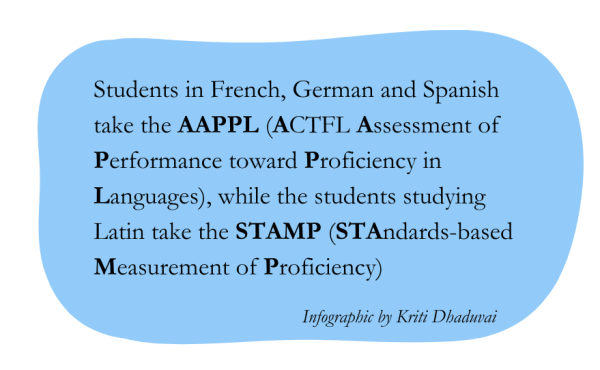

If you are in level four or five of a World Languages class, you may have encountered the AAPPL or STAMP tests. In the past years, these tests used to be administered only to students who chose to do Seal of Biliteracy. This year, however, all students in levels four and five of the World Languages classes were required to take this assessment in class.

The test functions as a district mandated program evaluation that can help give insight into how effectively the World Languages program is teaching students to be users of another language.

“The idea was that this test, which is already the Seal of Biliteracy, could be useful with that, being a less subjective way of measuring students’ growth in their languages,” Williamson said.

Spanish teacher Andrea Williamson is the co-leader of the World Languages department. She believes that these tests can more objectively measure how well a student is doing in their language.

“It’s more objective because I’m not grading my own students,” Williamson said. “My relationship with a student is just removed from my evaluation of their performance on that day.”

While a more objective evaluation can be a positive, standardized tests often fail to take into account the “test-taking factor,” as Williamson puts it. “It’s a nerve-wracking experience to take a standardized test,” she said. “So, in that moment, is the student remembering the coaching on how to take the test? Or is it that nervousness that overcomes them, and they kind of revert back to the most basic language that they are comfortable with using?”

The goal of the AAPPL and STAMP is to measure the students’ proficiency in a language. This means that students won’t know what the questions on the test will be asking, so that they can display their true language abilities to the greatest extent.

“Proficiency removes that ‘I know what to expect’ element out of it. You have to take all of your vocabulary knowledge and skills and synthesize them for the question you’re asked,” Williamson said. “So, it’s less easy to know what to expect, and therefore, it is a better proficiency measure because proficiency is like, how do you use language in a real world setting.”

Initially, most students were stressed about the assessment, however, some also saw the benefit of this testing style.

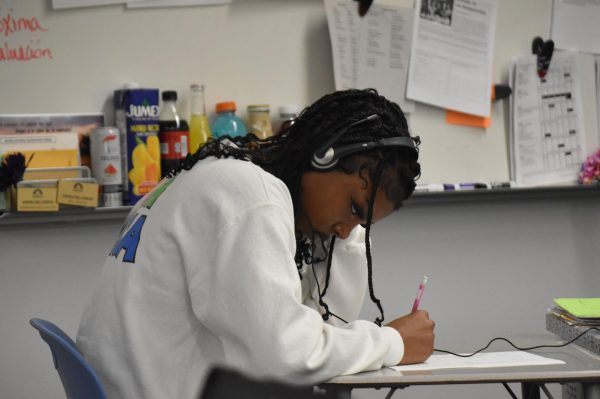

“Unlike our tests in (Spanish) class, the AAPPL test kind of forces you to entirely do it on your own with no external help. So, I think that’s a good thing in a way, because that forces you to see your true ability to do Spanish without any outside cheating, translations or your teachers helping you,” senior Malini Satheeskumar said.

From the students who took the AAPPL, most felt that the interpersonal speaking section of the assessment was more challenging.

“Everything, except for speaking, was easier than I thought I’d be. (For the) speaking, I kind of thought it would be a little bit harder than the rest but it was significantly harder,” sophomore Deepshikha Banerjee said.

Soon after the testing in classes was done, students received their score reports from the test. Many were surprised to see that their scores reflected a higher level of proficiency than they expected.

“When I got my scores back, I actually got some pretty high scores in the reading, writing and listening sections, which, I thought I failed all of them,” Satheeskumar said.

“I knew I’d do really good on listening and reading because those are basically easy,” Banerjee said. “(For the) speaking, I expected it to be pretty bad; I was surprised I passed.”

The score reports of the students overall provide valuable data for teachers to understand how well the program has been doing.

“I think it confirms what we already know,” Williamson said. “ (From) teaching kids that are in our classroom, we already know that speaking is the weakest skill among our students. What it (the test) doesn’t do is it doesn’t give us a ‘why’ that is. So we, as teachers, can speculate what we think the reasons are.”

To no one’s surprise, COVID might have had a significant impact on the language learning of most students who are taking languages in levels four or five this year.

“This year’s level four students had virtual learning in their very foundational levels. I personally feel — because that was such a difficult platform for learning a language — that it just kind of was an extra hurdle that students have had a hard time overcoming,” Williamson said.

Many students believe that the curriculum might be the reason their fundamental skills aren’t as strong.

“They (Spanish levels 1-3) kind of focused more on different units like weather and food as opposed to grammar,” Satheeskumar said. “I feel like if grammar is set up at the beginning, as opposed to at the end, then we have a good, solid foundation, as opposed to doing it in reverse.”

However, as the scores have only been recently released, there is not yet any solid plan to make changes based on the data collected from these tests.

“I think that is definitely something that we’re gonna get together and talk about to see: is there something that we should be doing a little bit differently or that we could be doing better?” Williamson said.

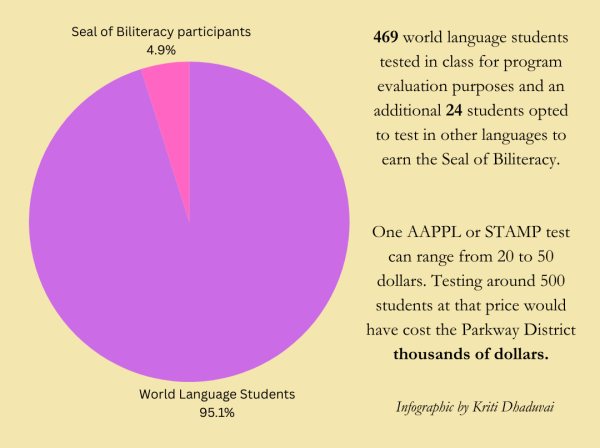

The AAPPL, STAMP, and other tests for the Seal of Biliteracy are created by independent testing companies, so it cost the District a lot of money to implement testing in classrooms for so many students. Nevertheless, it seems to provide valuable data on how well the current curriculum and teaching methods are working for students.

Therefore, it still remains to be decided whether or not students will continue to take these tests in class in the future.