In a world where there is an increasing amount of pressure for kids to succeed in school, where standardized testing is under scrutiny, and students are finding immense success in things that have nothing to do with their high school education, there’s some debate about the reliability of the traditional grading system. Should a student be able to graduate high school if they don’t technically meet all of the requirements, but demonstrate a nontraditional type of intelligence? Are teachers changing their curriculum so that kids don’t feel the pressure of conforming to a “normal” education, even if that’s not what they really need? Reports across the country indicate a concerning trend: teachers feeling pressured to pass students who may not meet the academic standards required for progression. This phenomenon, often termed “grade inflation,” raises questions about educational integrity and the true meaning of academic achievement.

This sentiment is echoed in a national survey conducted by the National Education Association (NEA), which found that 78% of teachers reported feeling pressure to inflate grades to ensure students pass. The reasons behind this pressure include situations such as school funding often being tied to graduation rates, creating incentives for administrators to push for higher pass rates. Additionally, the fear of backlash from parents and students, especially in an era where parental involvement is highly emphasized, adds to the strain on teachers.

Luckily for students and teachers in Parkway, though, this issue does not seem to be reflected in our hallways. Math teacher Alexandria Elder teaches Algebra 1, a class at Central with one of the highest fail rates, which is not something that she or administrators believe should be fudged, considering the extra help they receive in order to give them the opportunity to improve their grade on their own.

“I have always had the support of all of my coworkers to either pass or fail students,” Elder said. “I often call students into Ac Lab to work on individual skills that students need help with. I also communicate regularly with parents and keep everyone in the loop about the grades.”

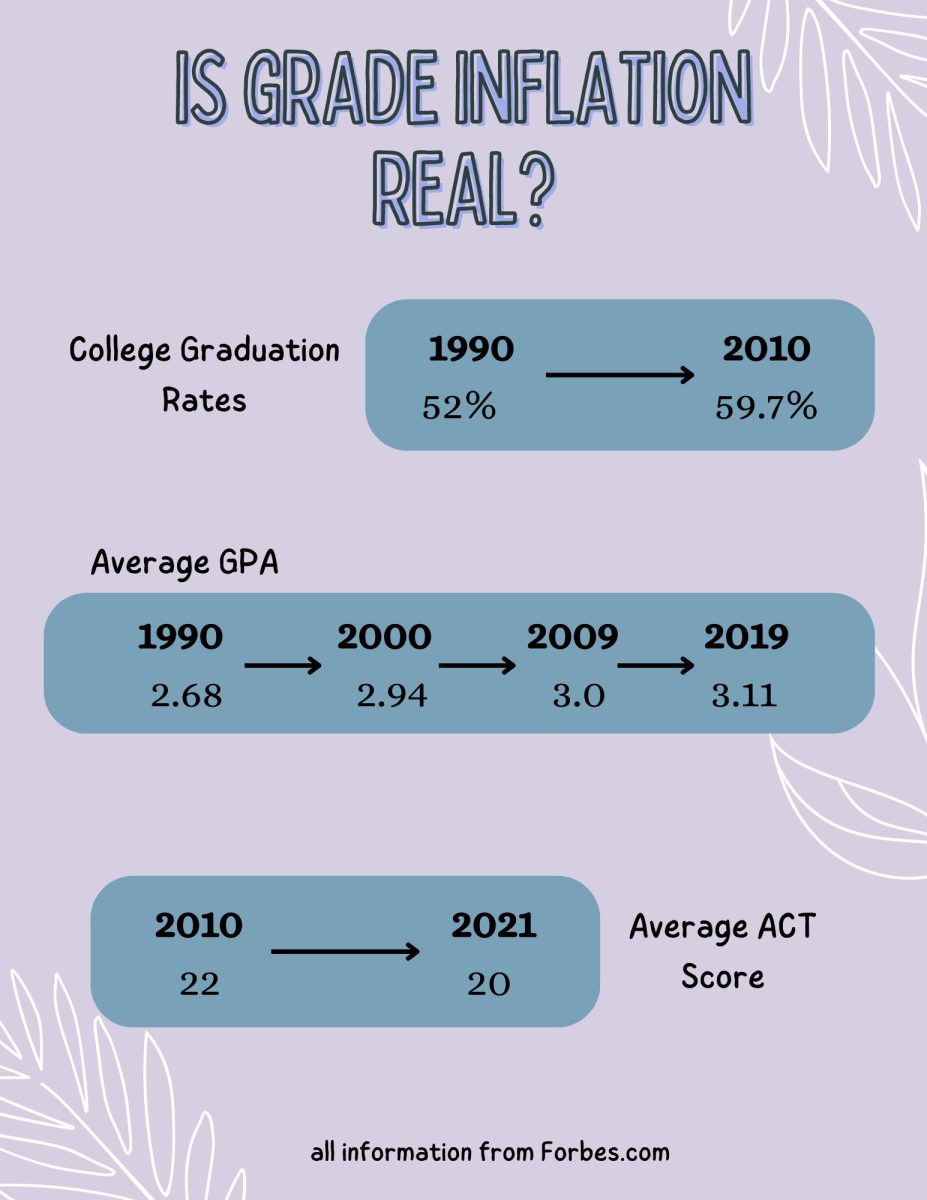

Nationwide, however, either students are becoming massively smarter despite the age of “screenagers” and laziness, or there is a separate issue occurring. A study published in the Journal of Educational Psychology found that the percentage of high school students graduating with an “A” average has risen from 38.9% in 1998 to 47% in 2016. This upward trend suggests a systemic shift towards grade inflation.

The consequences of grade inflation also extend beyond the classroom. There is the argument that inflating grades devalues the meaning of academic achievement, creating a culture of entitlement among students. Additionally, grade inflation has implications for college admissions. Admissions officers increasingly scrutinize applicants’ transcripts to discern genuine academic prowess from inflated grades. This has led many colleges to implement more holistic review processes, considering factors beyond grades and test scores alone.

In response to these concerns, educational policymakers are grappling with potential solutions. Some advocate for greater transparency in grading practices, encouraging schools to publish grading policies and criteria for promotion. Others emphasize the importance of professional development for teachers, equipping them with strategies to maintain academic standards while navigating external pressures.

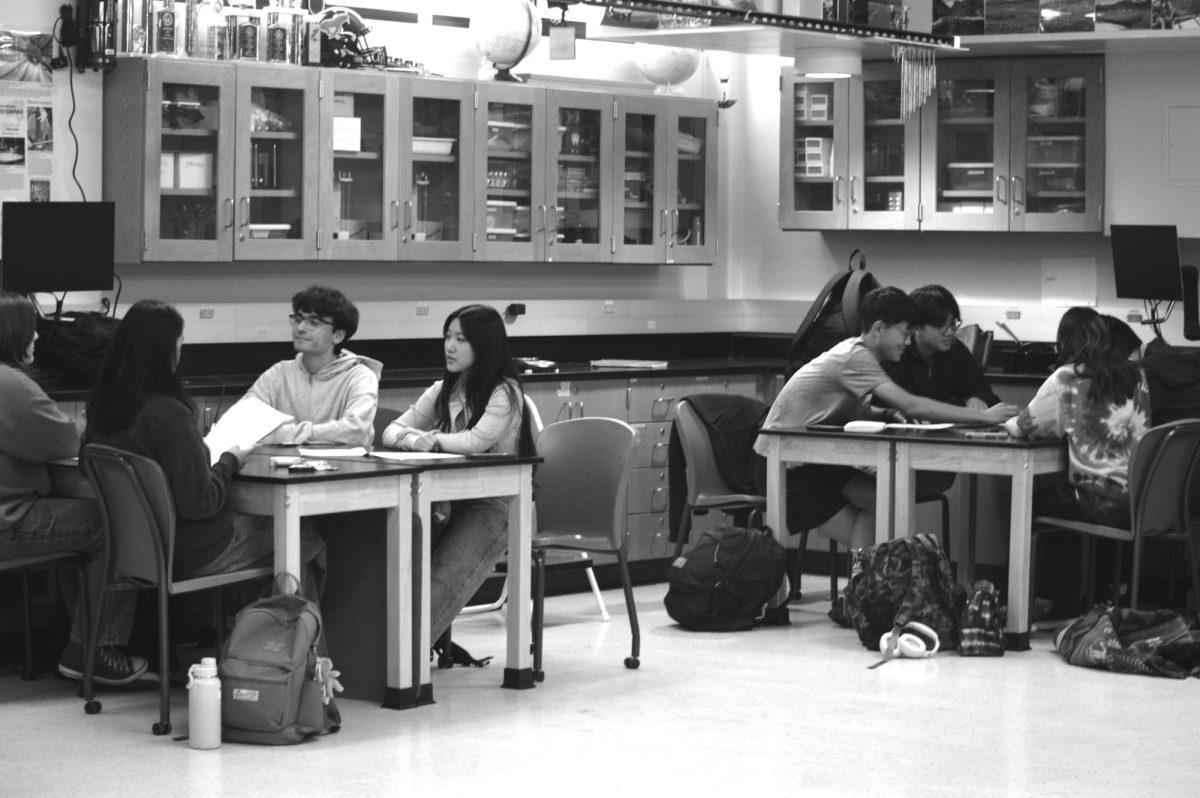

Science teacher Mollie Oakeley also teaches a class with a significant fail rate, but that doesn’t stop her from having integrity with her grading while also noticing what students need in order to be successful, especially in a class that is required for graduation.

“I allow students to turn in late labs to help boost their grade,” Oakeley said. “If I notice a student who is teetering between passing and failing the course, and only if they’ve shown me they’re willing to put in the work, I will allow them to return to old units and complete their missing labs if they have any.”

At the heart of this debate lies a fundamental question: What is the purpose of education? Is it merely to push students through the system, regardless of their future goals? Or is it to cultivate critical thinking, intellectual curiosity, and a genuine love for learning? As the conversation around grade inflation continues, one thing remains certain: the integrity of our education system hinges on a collective commitment to uphold academic standards, even in the face of external pressures. Only then can it be ensured that every student receives the quality education they deserve, and not just on paper.